In November, Qatar entered the third and last year of its technical cooperation program with the International Labour Organization (ILO) aimed at extensively reforming migrant workers’ conditions including by replacing the kafala (sponsorship) system, which gives employers extensive powers over migrant workers, with a new contractual system.

Migrant Workers

However, the kafala system remains in place and continues to facilitate the abuse and exploitation of the country’s migrant workforce. Families from the Ghufran clan remain stateless and deprived of key human rights 20 years after the government stripped them of their citizenship.

Qatari laws continue to discriminate against women and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals. Throughout 2019, the diplomatic crisis persisted between Qatar on one side and Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on the other, over Qatar’s alleged support of terrorism and ties with Iran, impacting the rights of Qataris and other Gulf and Egyptian nationals too.

Qatar has a migrant labor force of over 2 million people, who comprise approximately 95 percent of its total labor force. Approximately 1 million workers are employed in construction while another 100,000 are domestic workers. The kafala system governing the employment of migrant workers gives employers excessive control over them, including the power to prevent them from changing jobs, escaping abusive labor situations, and, for some workers, leaving the country.

In October 2017, the International Trade Union Confederation announced Qatar’s agreement with the International Labour Organization (ILO) to substantially reform the current kafala system, institute a nondiscriminatory minimum wage, improve payment of wages, and end document confiscation and the need for an exit permit for most workers wanting to leave the country. The agreement called for stepped-up efforts to prevent forced labor, enhance labor inspections and occupational safety and health protocols—including by developing a heat mitigation strategy—and refine the contractual system to improve labor recruitment procedures.

Since then, the government has introduced several reforms. They include in 2017 setting a temporary minimum wage, introducing a law for domestic workers, and setting up new dispute resolution committees; in 2018 establishing a workers’ support and insurance fund, and ending the requirement for most workers to get their employer’s permission to leave the country; and in 2019 mandating the establishment of joining labor committees at companies employing more than 30 workers for collective bargaining, and disseminating enhanced guidelines on heat stress aimed at employers and workers.

While positive, these reforms have not gone far enough, and implementation has been uneven. The 2017 domestic workers law is poorly enforced and does not meet international standards. The workers’ support and insurance fund, introduced in October 2018 to make sure workers receive wages when companies fail to pay, is not yet operating. Authorities are failing to enforce bans on passport confiscations and workers’ paying recruitment fees. Most importantly, the kafala system by and large remains in place. The partial reform of the exit permit system does not apply to domestic workers, government employees, and up to 5 percent of any company’s workforce who still need their employer’s permission to leave the country. While others no longer need an exit permit, they may not be able to leave if their passports are confiscated.

The heat stress guidelines are also not comprehensive or obligatory for employers and do not come with any enforcement mechanisms. In 2019, Qatar continued to enforce a demonstrably rudimentary midday summer working hours ban. Moreover, for six years, Qatar has not made public meaningful data on migrant worker deaths that would allow an assessment of the extent to which heat stress is a factor. However, new medical research published in July 2019 concluded that heatstroke is a likely cause of cardiovascular fatalities among migrant workers in Qatar.

Qatar’s labor law does not guarantee migrant workers the right to strike and to free association. In August 2019, despite a ban on migrant workers striking, thousands of workers employed by at least three different companies went on strike to protest poor working conditions, unpaid and delayed wages, and threats of reduced wages.

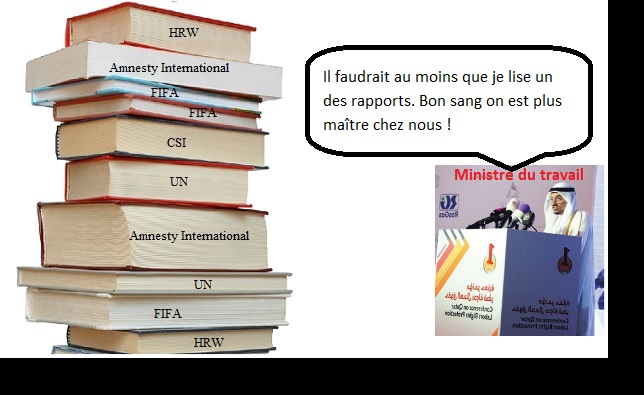

On October 16, 2019, the ILO announced that Qatar’s Council of Ministers endorsed new legislation that would allow workers to change employers without employer consent, and a new law to establish a non-discriminatory minimum wage. The legislation, which still requires approval by Qatar’s Shura (Advisory) Council and sign-off by the Emir, is expected to come into force by January 2020. According to the statement, a ministerial decree by the minister of interior was also signed, removing exit permit requirements for all workers, except military personnel.

Women’s Rights

Qatar allows men to pass citizenship to their spouses and children, whereas children of Qatari women and non-citizen men can only apply for citizenship under narrow conditions, which discriminates against Qatari women married to foreigners, and their children and spouses.

In September 2018, Qatar passed a permanent residency law that for the first time provides that children of Qatari women married to non-Qatari men, among others, can apply for permanent residency allowing them to receive government health and educational services, to invest in the economy, and own real estate. However, the law falls short of granting women equal rights to men in conferring nationality to their children and spouses.

The concept of male guardianship is incorporated into Qatari law and regulations and undermines women’s right to make autonomous decisions about marriage and travel. Qatar’s personal status law also discriminates against women in marriage, divorce, child custody, and inheritance. The law provides that women can only marry if a male guardian approves; men have a unilateral right to divorce while women must apply to the courts for divorce on limited grounds; and a wife is responsible for looking after the household and obeying her husband. Under inheritance provisions, female siblings receive half the amount their brothers get. Single women under 25 years of age must obtain their guardian’s permission to travel outside Qatar. While married women at any age can travel abroad without permission, men can petition a court to prohibit their wives’ travel. A wife can be deemed disobedient, and thus lose her husband’s financial support, if she travels despite his objection.

Qatar has no law on domestic violence and only has an article in the family law forbidding husbands from hurting their wives physically or morally, and general provisions on assault.

Refugee Rights

In September 2018, Qatar’s emir signed into law the Gulf region’s first asylum law. The law demonstrates Qatar’s intention to refugee rights but falls short of its international obligations, particularly with regard to its restrictions on freedom of movement and expression. Qatar is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

In April 2019, Qatar introduced two ministerial decrees determining the categories of individuals who have the right to obtain asylum and laying out the benefits and rights afforded to asylees. According to the National Human Rights Commission, the committee necessary to determine asylum claims was established in May and started to receive cases in August. However, some individuals who tried to apply for asylum said Ministry of Interior officials turned them away, telling them on multiple occasions that the law had not yet been put into practice. Throughout 2019, the Interior Ministry’s search and follow up department repeatedly threatened two individuals with deportation without cause and despite both individuals’ stated desire to seek asylum under the new law.

Statelessness

Qatar’s decision to arbitrarily strip families from the Ghufran clan of their citizenship starting in 1996 has left some members still stateless 20 years later and deprived them of key human rights. In 2019, Qatar made no commitments to rectify their status.

Stateless members of the Ghufran clan are deprived of their rights to work, access to health care, education, marriage and starting a family, owning property, and freedom of movement. Without valid identity documents, they face restrictions accessing basic services, including opening bank accounts and acquiring drivers’ licenses, and are at risk of arbitrary detention. Those living in Qatar are also denied a range of government benefits afforded to Qatari citizens, including state jobs, food and energy subsidies, and free health care.

Qatar is not party to the 1954 or the 1961 UN Statelessness Conventions. Its laws on nationality say nothing about revoking citizenship when that would leave the person stateless.

Sexual Orientation and Morality Laws

Qatar’s penal code criminalizes sodomy, punishing same-sex relations with imprisonment for one to three years. Individuals convicted of zina (sex outside of marriage) can be sentenced to prison. In addition to imprisonment, Muslims can be sentenced to flogging (if unmarried) or the death penalty (if married). Women are disproportionately impacted as pregnancy serves as evidence of extramarital sex and women who report rape can find themselves prosecuted for consensual sex instead.

Under Article 296 of the penal code, “[l]eading, instigating or seducing a male anyhow for sodomy or dissipation” and “[i]nducing or seducing a male or a female anyhow to commit illegal or immoral actions” is punishable by up to three years. The law does not penalize the person who is “instigated” or “enticed.” It is unclear whether this law is intended to prohibit all same-sex acts between men, and whether only one partner is considered legally liable.

Section 47 of the 1979 Press and Publications Law bans publication of “any printed matter that is deemed contrary to the ethics, violates the morals or harms the dignity of the people or their personal freedoms.” Throughout 2018, private publishing partners in Qatar, including the partner of the New York Times, censored numerous articles that touched on LGBT topics, in line with the country’s anti-LGBT laws.

Key International Actors

In June 2019, the crisis pitting Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, and Egypt against Qatar entered its third year. Travel between these countries and Qatar remains restricted, and the land border with Saudi Arabia remains closed. Qataris can only visit relatives in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE if they obtain those governments’ permission explaining the “humanitarian” reason for their trip. In UAE and Bahrain, speech critical of their governments’ isolation of Qatar or expressing sympathy for Qatar is prosecuted as a crime.

Qatar and the United States signed a number of bilateral agreements, including on civil aviation, counterterrorism, and cybersecurity. In January 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo signed a memorandum of understanding with Qatar regarding the expansion and renovation of al-Udeid Air Base, the largest US military base in the region.